7 June 2025 - Advocacy

The long-awaited report by the Italian Parliamentary Committee for the Security of the Republic (COPASIR) on the use of Graphite spyware is now public. Yet rather than clarifying events, the document raises further concerns about government accountability, the cost of surveillance, and the extent of state overreach. Below we highlight some of the most troubling findings. The full report is available on the website of the Italian Parliament (in Italian).

The report confirms that Luca Casarini, a prominent figure in the humanitarian NGO Mediterranea Saving Humans, was intermittently placed under surveillance for at least five years. Initially, traditional methods were used; under the current government, however, the highly invasive Graphite spyware was deployed. Mediterranea is no secretive organization: its search and rescue missions in the Mediterranean are conducted under the watch of international observers and journalists.

This raises serious questions about what could justify such a prolonged and intrusive operation targeting an organization whose goals and methods are transparent and lawful. The mismatch between the invasive tools employed, the years-long duration of the operation, and the meager investigative results is alarming — and difficult to justify.

The Italian government has made conflicting and shifting statements regarding the spyware scandal. At first, it downplayed the existence of any victims; then, it acknowledged that contracts with the Israeli spyware vendor Paragon were still in effect. Later, it claimed the contracts had been suspended. According to Haaretz, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni even contacted Netanyahu directly to seek clarification.

The COPASIR report, however, offers a different account: it states that the contract was unilaterally terminated by the Italian intelligence agencies, contradicting the government’s earlier version of events.

The report devotes considerable attention to the “traceability” of actions carried out using Graphite spyware:

Another legal issue related to the use of modern interception technologies, as emerged during hearings, is that data are saved in non-deletable databases by the public agencies using the system, unless the service provider is involved in the deletion process (p. 23, translation from Italian)

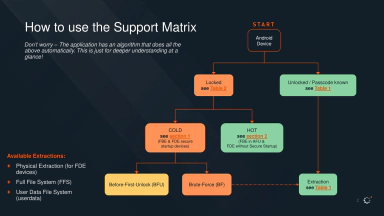

According to the information gathered by the Committee during its inquiry, every use of the Graphite spyware is logged: the operator must authenticate with a username and password, and each operation is recorded in a database or “acquisition log” and in an audit register. The database is located on the client’s premises, collects information about the target, and is not accessible to the company. The audit log, which is also hosted on servers located at the client, records all operations and system accesses, including technical access for maintenance or updates by the company. Furthermore, data in the database can be deleted by the client, but audit logs cannot be altered by the client. During site visits to the agencies on May 7, 2025, the Committee specifically requested and obtained assurances that the contents of the operations would not be accessible to Paragon Solutions. (p. 13, translation from Italian)

But such assurances are fragile. The absence of a graphical interface to modify audit logs does not guarantee their immutability. If the audit system is under the client’s control, anyone with sufficient access could tamper with it—especially given that several months passed between the initial media exposure (January 31) and the start of any formal investigation. Only an independent forensic analysis could credibly verify the integrity of these logs.

One striking example is the case of journalist Giovanni Cancellato, officially deemed not to have been targeted, according to COPASIR. The explanation offered is that his device appeared in the detection results due to “false positives.” Yet his phone was not the only one affected as multiple members of his newsroom also showed signs of compromise.

Is it reasonable to expect private citizens or NGOs to provide definitive “proof” in cases where the very nature of spyware is to remain invisible, leave no trace, and render verification nearly impossible? This dynamic shifts the burden of proof to the victim, while conveniently sparing those with full operational control and privileged access from further scrutiny.

The naïveté of such claims would be ironic, if not outright offensive, given the double standards they reveal. Authorities would never settle for a graphical confirmation in lieu of a forensic audit if it were a citizen or activist under investigation. Yet here, the possibility of tampering isn’t even considered. Victims and overburdened NGOs (often assisting hundreds of cases worldwide) are expected to conduct even deeper forensic investigations, despite the abundance of circumstantial and corroborating evidence: multiple infected journalists, a Meta notification, and partial independent confirmation by Citizen Lab.

One passage from the report is particularly alarming:

Phone numbers with an Italian prefix are not among those contractually excluded from being subjected to surveillance through Graphite spyware. (p. 18, translation from Italian)

In plain terms: to prevent Italian citizens from being spied on by Paragon’s foreign clients, the Italian state must pay. The only way to exempt a country code from the list of potential surveillance targets is to negotiate and pay for a contractual exclusion.

This reveals a business model based on extortion: if a government doesn’t pay, its citizens remain vulnerable to being targeted by foreign governments using Paragon’s tools.

In the meantime, Paragon has publicly responded to the COPASIR investigation, claiming it had offered technical cooperation to Italian authorities to verify whether its spyware had been used against Francesco Cancellato, and that it terminated its contract with Italy after the authorities declined to proceed.

These statements should be treated with caution, as Paragon is a directly involved party with a clear interest in protecting its commercial image. However, on one point we agree: the investigation into the Fanpage journalists remains inadequate. And once again, we see conflicting versions from Paragon and the Italian government, raising more questions than they answer.

Once again, advanced surveillance tools are being used against activists and journalists, not just in the exceptional cases that are often cited to justify their deployment. As previous cases in Poland, Spain, Greece, and elsewhere have shown, often in democratic countries spyware is used to target dissenting or inconvenient voices—with enormous financial costs, dubious investigative outcomes, and serious risks to global cybersecurity.

The Italian government must take responsibility, provide full transparency on the actual use of Graphite, and immediately end all contracts with companies like Paragon. The European Union should act—as urged by Citizen Lab—to restrict the use of such technologies, ban their production within Europe, and sanction the companies involved.

You’ve read an article from the Advocacy section, where we defend online privacy and anonymity, document threats and invasive practices such as surveillance companies, and promote a conscious and free digital culture.

We are a non-profit organization run entirely by volunteers. If you value our work, you can support us with a donation: we accept financial contributions, as well as hardware and bandwidth to help sustain our activities. To learn how to support us, visit the donation page.