16 March 2025 - Research

The widespread use of Cellebrite software is not a secret: we mentioned it very recently, as did Amnesty in their recent report covering abuses towards civil society and detailing vulnerabilities exploited. This blogpost is the first in a series of two: here we’ll explore the general history and development of the company, while in the second one we will provide a more detailed list of its capabilities updated as of February 2025. Cellebrite is not alone in this market; other competitors, especially regarding exploitation, include Greykey (previously Greyshift), recently acquired by Axon and integrated into Magnet Forensics.

Our recent interest in Cellebrite arises from two key developments. First, we have seen a surge of activists asking us to examine phones that were returned after being seized. Second, sources familiar with the matter have confirmed that, following the recent Paragon scandal in Italy, Cellebrite has attempted to reassess its customer vetting practices. However, particularly in Italy, there have been longstanding reports of erratic sales policies and practices. To understand this, let’s take a step back: companies like Cellebrite operate in a largely unregulated market. While their primary customers are law enforcement agencies, their target customer base extends to a wide range of private companies and individuals. This raises significant concerns, as some of these customers may be operating outside the law—yet, in most cases, there is no oversight to hold them accountable.

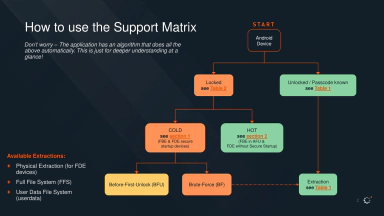

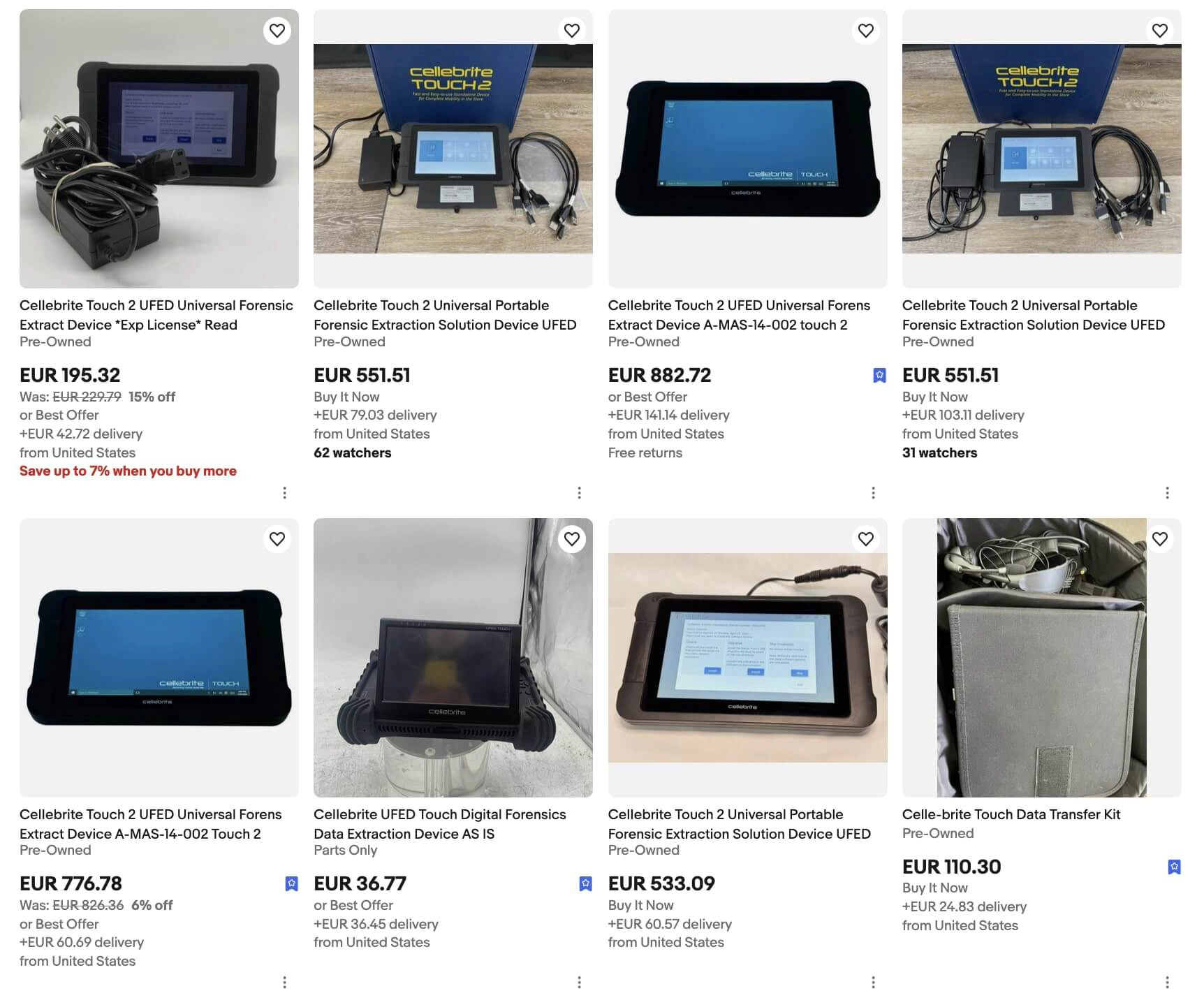

The line of products sold by the company has undergone multiple rounds of rebranding and structural changes over the past four years, particularly since Signal published their research about it. Cellebrite has been in the market for a long time, initially focusing on dedicated hardware for efficient forensic extraction from mobile devices, even before smartphones existed. If you buy any of their older devices, you might be surprised to find that even end-of-life products, such as the relatively recent UFED Touch 2, still include cables for extracting data from Nokia 1100 phones. While forensic analysis has always been central to their business model, the need to unlock devices and bypass cryptography is a relatively recent development.

While, as far as we know, Cellebrite used to ship known exploits or unlocking methods for older models, the introduction of mandatory file-based encryption (FBE) and secure elements has shifted the approach to mobile security. Rumor has it that, while there was already demand in the market and some companies were involved, many were primarily repurposing jailbreaks, known chipset vulnerabilities, and similar techniques to achieve their goals. However, checkm8 changed the game for the entire industry—it made it possible to unlock all iPhones from the 4S up to the X, regardless of the software patch level. With these tools freely available and easily accessible, competitors—and even law enforcement agencies themselves—could perform the unlocking and extraction without relying on specialized vendors. As the market became more competitive, companies realized they needed to step up their game to retain and expand their customer base. This led to a significant increase in research efforts focused on acquiring and developing 0-day and 1-day vulnerabilities.

While the exploits required for these types of attacks are often very different from those used in spyware infections, since they rely on hardware access rather than message-based, browsing-based, or similar entry points, they are not necessarily simpler, especially for Apple devices. For Android, being based on Linux, things seem relatively more accessible due to a larger attack surface. This includes a wide range of USB-based drivers that have undergone little to no scrutiny over the years and are still shipped by default, often remaining loaded even when a phone is locked. Recent reports from Amnesty have highlighted these vulnerabilities. However, advanced mitigations, such as memory tagging and other new security features on Pixel phones, are making exploitation increasingly difficult.

And here we arrive at the second major issue in this market: previously, Cellebrite kept its most valuable vulnerabilities private, requiring customers to physically ship the devices they wanted unlocked to certain locations. Additionally, the exploitation process was largely manual: human analysts would identify devices and attempt to determine the most suitable unlocking and extraction method if it was not already covered by the suite provided to customers. This approach proved problematic for several reasons. First, some customers were unwilling to send their devices across borders, as it could compromise the chain of custody. Second, in most democracies, defendants have the right to be present during non-reproducible forensic analyses that might alter evidence, something inherent to active exploitation attacks. Lastly, scalability was a major limitation, both due to the human effort required and the delays caused by shipping. From a business standpoint, an automated solution would have benefited both Cellebrite’s operations and its customers.

But this presents a fundamental challenge: if Cellebrite simply shipped its exploitation capabilities with their software suite, even with extensive obfuscation, skilled researchers could quickly reverse-engineer their vulnerabilities and expose them. This could happen either out of a commitment to security and democratic principles or, ironically, to collect bug bounties. As far as we know, Cellebrite has long used custom-made cables and, more recently, has attempted to enhance its capabilities with single multi-purpose adapters required for deploying their attacks. These hardware dependencies also make it more difficult for cracked versions of their suite to proliferate—something we have firsthand witnessed as being far from uncommon.

However, as long as the core logic had to run on the customer’s computer—or even on a dedicated tablet, as marketed in previous generations—it remained relatively easy to extract and analyze.

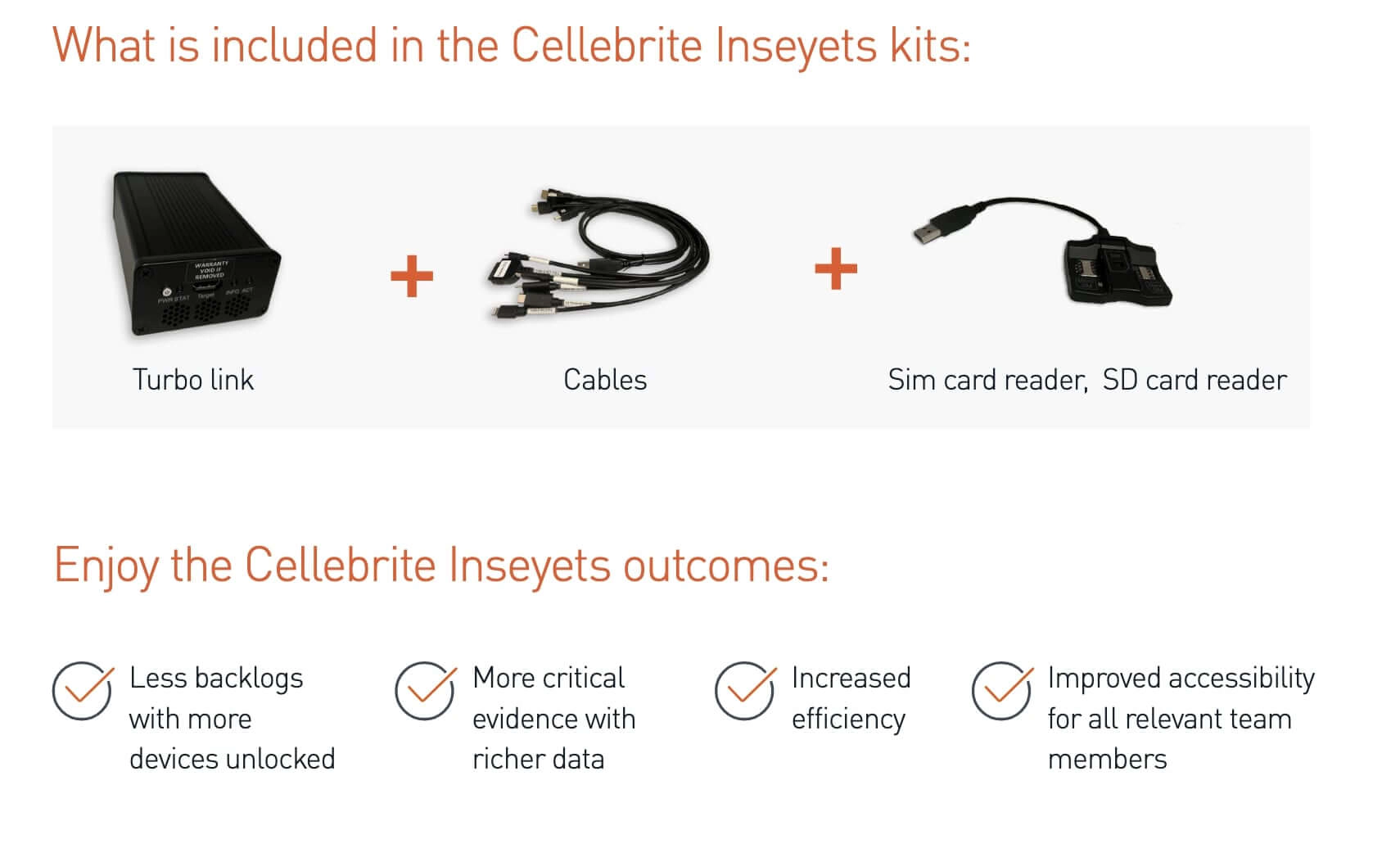

Here comes the idea: since tablets and similar devices were highly impractical and had limited resources, while current Inseyets software might require up to 128GB of RAM and 24-core Threadripper CPUs to run smoothly on large pieces of evidence and probably to support their “magic AI” (even generative AI, which, of course, would never hallucinate—especially in cases where people’s futures are at stake), they opted for a hybrid approach.

Instead of moving the entire suite to a dedicated appliance, Cellebrite decided to keep the main software running on the customer’s hardware. However, for selected customers permitted to purchase the Premium package (or whatever it is currently called—whether Premium Advanced Access, Advantage, Advanced Logical, or perhaps Premium ES, also known as Mobile Elite), they now ship a specialized embedded device: the Turbo Link.

As we will see in the next post, the new software suite, along with the Turbo Link adapter, fully streamlines exploitation and extraction. The exploits likely never transit in cleartext on the customer’s machine and are only delivered when necessary, after the target device has been identified. From the limited pictures available, the Turbo Link appears to be actively cooled and includes an HDMI port, which requires a secondary cable from the kit to connect to the target device. A reasonable assumption about this setup is that exploits are likely end-to-end encrypted from Cellebrite’s servers to the Turbo Link device, which itself probably has to guarantee a certain level of both software and hardware integrity.

According to Amnesty, the use of an HDMI port is to simplify the emulation of media peripherals, often used for exploitation. On the other side, it is connected via USB to the customer’s computer. However, for customers who wish to scale beyond their contracts—or for those needing to unlock devices while being offline—Cellebrite also sells licenses for a centralized network server called the Enterprise Vault Server (EVS). According to the brochure and their promotional videos, it “supplies the resources necessary to gain access to advanced iOS and Android devices.”

We have explored some of Cellebrite’s history and business structure. In the next post, we’ll take a more practical look at how this translates into their current capabilities. In the coming months, we will publish mitigation strategies and guides to help you and your communities defend against these types of threats.

We’ll reiterate again: we strongly believe that vulnerability trading is intrinsically unethical, as it fuels a vicious cycle of insecurity that puts everyone at risk.

If you have information that could complement this piece, feel free to contact us. If you own old Cellebrite hardware that is end-of-life, or that no longer has a valid license, thus no longer useful, we are collecting older surveillance technology for archival purposes (more on this soon) and we will happily collect your e-waste. Visit the contacts page to discover how to get in touch with us securely.

You’ve read an article from the Research section, where we share the results of our technical and social investigations into networks, security, and surveillance, with the goal of deep understanding and public knowledge creation.

We are a non-profit organization run entirely by volunteers. If you value our work, you can support us with a donation: we accept financial contributions, as well as hardware and bandwidth to help sustain our activities. To learn how to support us, visit the donation page.